Tane’s story: The Real Face of Men’s Health

I’ve supported Movember because our stories, even the hard ones, can make people feel less alone. If sharing mine helps someone reach out, or feel seen, then it’s worth it. Be part of the solution at The Real Face of Men’s Health.

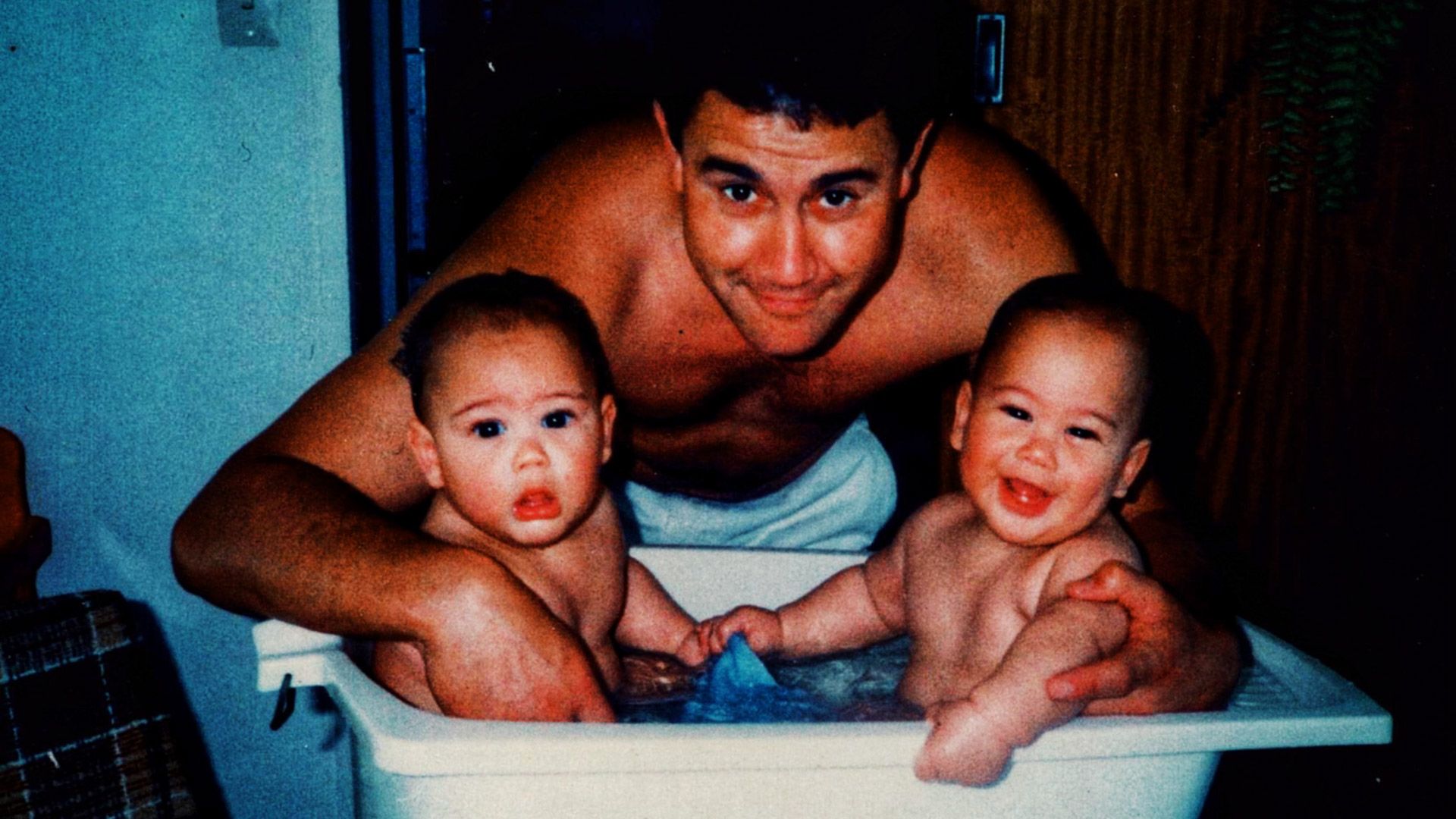

In Te Ao Māori, twins are sacred. The firstborn, the pēpi tuatahi, clears the path. The second, the pēpi tuarua, follows - pushed into the world by their sibling. I was born five minutes before my brother Tama. From the moment we arrived, we were inseparable.

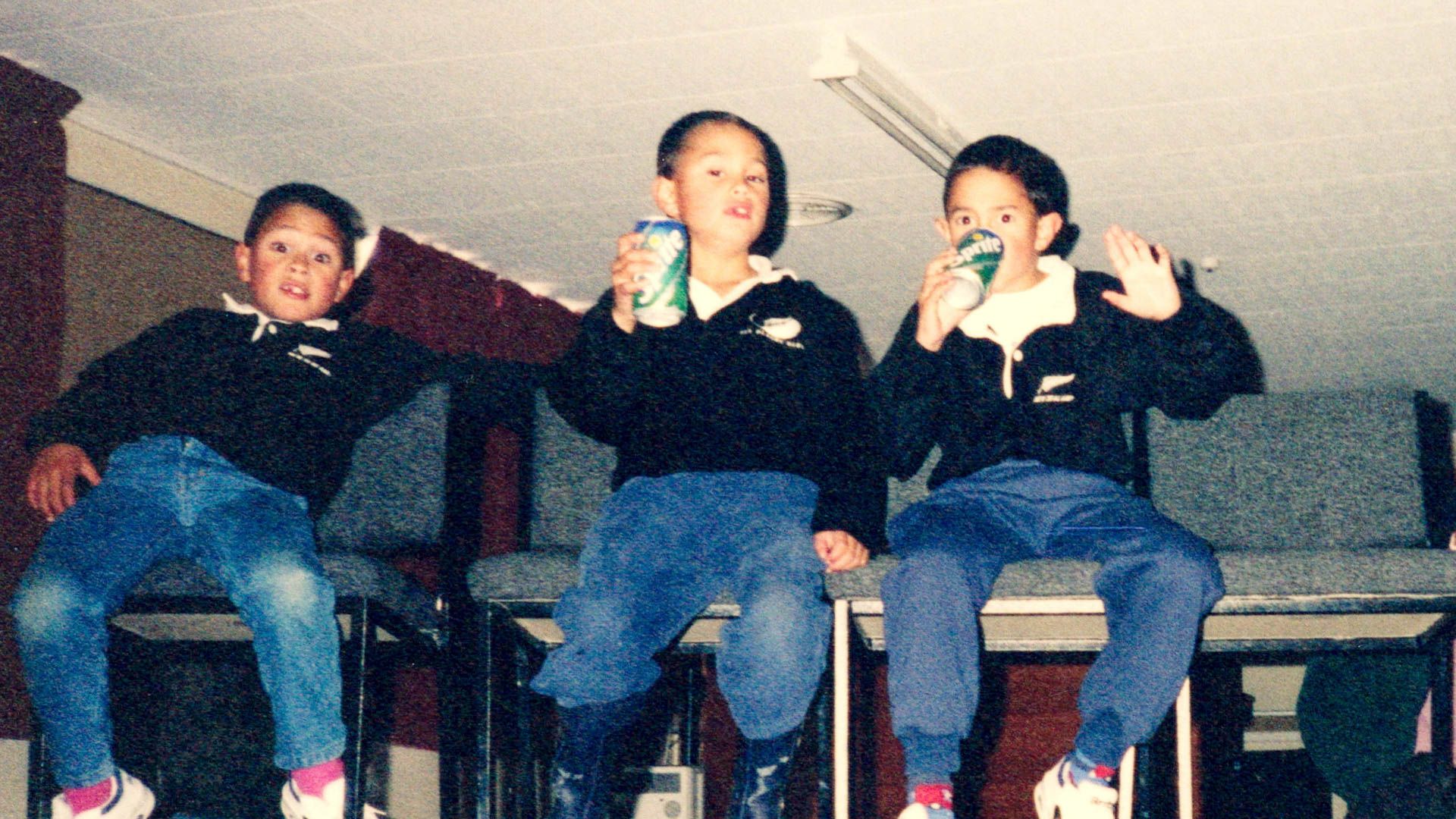

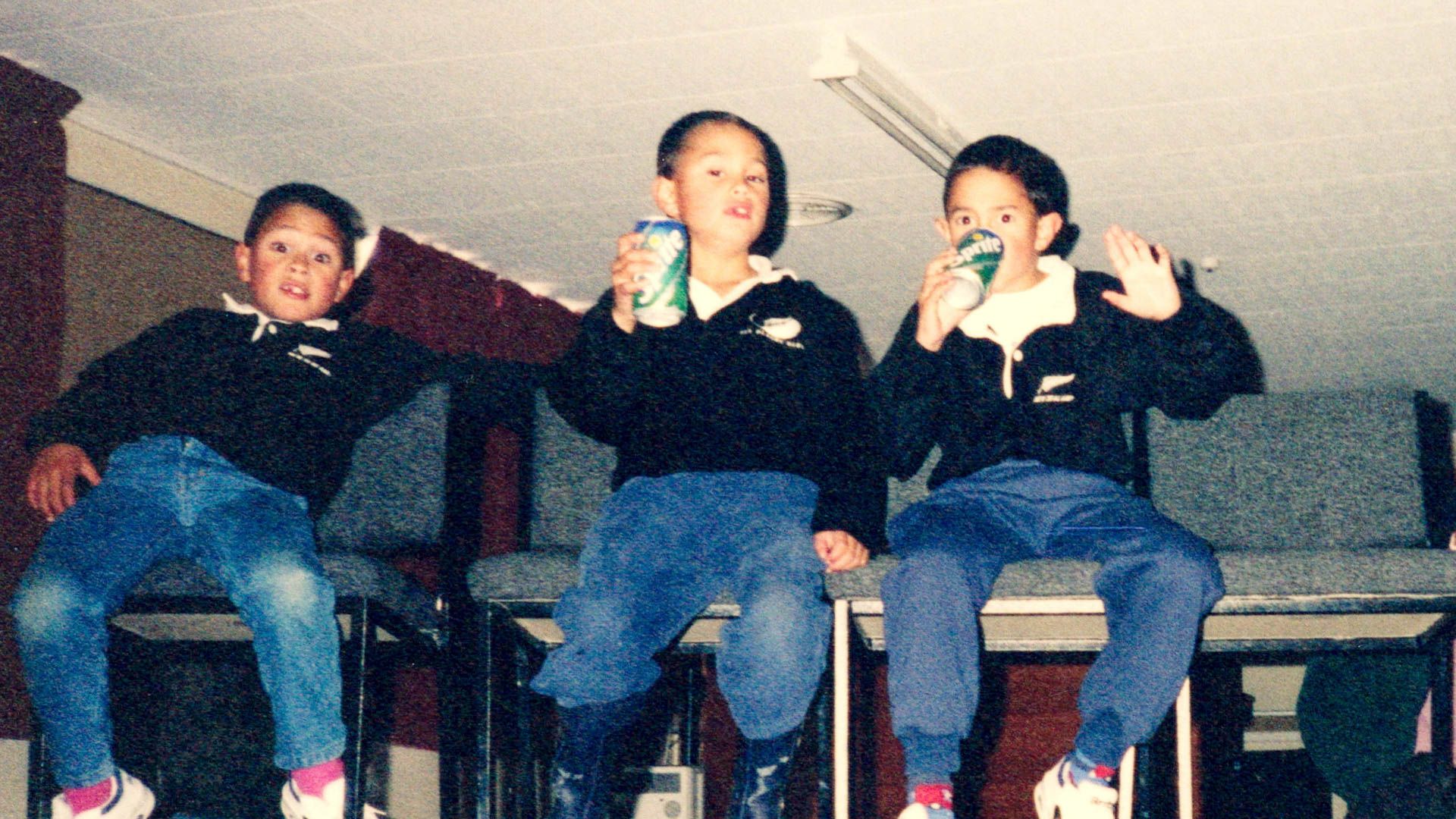

We grew up under the watchful eye of the twin peaks of Mount Ruapehu, biking, kicking the footy, and never missing an All Blacks game. We shared everything. Even as adults, that closeness stayed. Tama had this boundless energy and overwhelming kindness that sometimes made people uncomfortable. He gave everything of himself. He’d call, drive over, check in, gift people his favourite things just to show he cared. He was the guy you wanted on your team. In life and on the rugby field.

He played for the Lyttleton Rugby Club and would quietly score match-winning tries without ever talking about it. He was that guy. Full of heart, deeply loved by his teammates, and too humble to seek the spotlight.

" Full of life, always giving to others, but Tama never really talked about how he was feeling. Even with me. "

In June 2020, Tama ended up in the hospital. That was the first time we became aware of the depth of his declining mental health. In Te Ao Māori, when someone enters that vulnerable state, they’re in a tapu space. A sacred, fragile place. But once inside the health system, that sacredness often gets stripped away and replaced with deficit-based language: disorder, risk, struggle. It can be cold. It can make you feel like you are the problem, rather than someone who needs care.

Tama kept close to a few of his teammates and to me during that time. But support is difficult to sustain, especially in a system that’s fragmented and overloaded. As adults, it’s not easy to bring your full support network into that process. In some ways, we all entered the system that day. But none of us had a map.

Tama died by suicide in November 2020. The impact was profound. In the days after, I received over 500 messages. Friends and whānau rallied around us, but I was unravelling. I couldn’t look in the mirror. I had flashbacks. Nightmares. I lost my sense of self completely.

That was the beginning of my healing journey, a journey I do for both of us. The inroad to entering the system had so many barriers, many of which Tama would have faced, too. I thankfully went to my GP. I started counselling. I found medication that helped. I tried EMDR therapy. I built a support network online and had amazing friends check in regularly. Most importantly, I started trying to be my own best friend and to forgive myself when I wasn’t.

I don’t think Tama realised the depth of what he was facing. If we treated mental health like we treat physical health with urgency, compassion, and recovery at the centre, perhaps things would’ve been different. I’ve learned that language matters. When we frame mental distress as failure, sensitive people, people with already low self-esteem, may never speak up.

That’s why I chose to support the wellbeing workshop at Tama’s rugby club, and why I’m sharing this now. There is so much we can do to shift the culture: learn basic mental health first aid, build emotional capacity like we build physical strength, and develop better listening skills. These things save lives.

Tama was the best brother. I still buy him birthday presents. I’ve kept growing his jersey collection, and I’ve never thought of him as gone; I just feel him differently now. It’s a difficult journey, and while I feel the immense loss of some things, I also feel a deeper love and growth of a deeper connection with myself and others.

We were twins before we were born — and we always will be.

This is the Real Face of Men’s Health

We all have partners, fathers, brothers, sons, and mates that we love. When these men are well, the benefits ripple through relationships, families, and communities. But when these men are unwell and unsupported, we all feel it. When they do seek assistance, they often don’t get the support they need. And this puts enormous pressure on the families and communities who care for men.

It means we’ve got so many reasons to care about men’s health. And it’s why we must advocate for more public action to drive change.

Be part of the solution at The Real Face of Men’s Health.